What is the universe made of? SLAC experts weigh in on the mysterious force that shapes our cosmic history

Cosmologists Josh Frieman and Risa Wechsler look back on the Dark Energy Survey, sharing how it’s paving the way for the NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory to dig deeper into some of the universe’s darkest mysteries.

- Dark energy drives the accelerating expansion of the universe, making up about 70% of its total mass-energy content.

- The Dark Energy Survey (DES) was created to probe dark energy using a large optical survey, discovering dwarf galaxies and powerful ways to study dark matter.

- The NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s LSST will dig even deeper than DES to advance our knowledge of dark energy, dark matter and other cosmological phenomena.

As the Dark Energy Survey (DES) releases its final results, we caught up with two physicists who’ve been involved in the project from its early days. In this Q&A, Josh Frieman, DES co-founder and associate laboratory director for fundamental physics at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, and Risa Wechsler, a Humanities and Sciences Professor and professor of physics in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University, professor of particle physics and astrophysics at SLAC, and director of the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology, discuss what the decade-long effort taught us and how it prepares us for the NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s 10-year mission to explore some of the universe’s biggest mysteries.

What is dark energy and why is it important to study?

Josh: Dark energy is the name we give to a phenomenon that explains why the expansion of the universe is speeding up rather than slowing down. If only gravity were at play, the universe should be slowing because matter attracts matter. Instead, there is a gravitationally repulsive effect: dark energy.

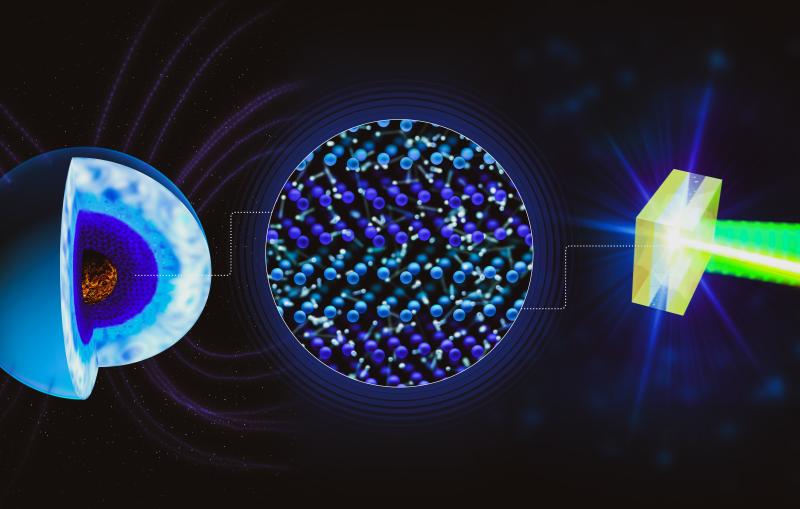

For this to occur, dark energy must make up about 70% of the total amount of mass-energy in the universe today (about 25% or so would be dark matter, and 5% would be atoms, the stuff we’re made of), which signals to me it’s something we should try to understand.

One of the oldest ideas for what dark energy might be goes back to Einstein, who added something to his equations called the cosmological constant – what we would now call vacuum energy, the energy of empty space. In classical physics that energy would be zero, but in quantum mechanics, even “empty” space has energy. When you work out its properties, that energy behaves just like dark energy: If it dominates the universe, it causes the expansion to speed up.

Risa: Observations show the expansion Josh describes started speeding up roughly halfway through the universe’s history, something matter alone can’t do.

The early universe was also very smooth; today it’s clumpy – full of galaxies, stars and planets. Our theories of gravity and cosmology tell us that how the universe expands and how it becomes clumpy depend on what it contains. Measuring both of those observational effects more precisely than we have in the past is one way to figure out what dark energy actually is. Those two effects motivated the Dark Energy Survey and other cosmology surveys we’re pursuing now.

How did the idea for the Dark Energy Survey come about?

Josh: The first hints for dark energy appeared in the early 1990s, and those hints turned into evidence through observations of just a few tens of distant supernovae in the late 1990s. But at that time, it was enough to reveal that the expansion of the universe was speeding up, a discovery that later earned the Nobel Prize.

The question became: What is dark energy, and how do we measure its properties? As Risa describes, you need to understand both the expansion history and the growth of structure. That requires a large cosmic survey of hundreds of millions of galaxies, along with thousands of supernovae, the original evidence for accelerated expansion.

In 2003, we started thinking about how to do this. A major motivation was a new cosmic microwave background telescope being built at the South Pole – the South Pole Telescope – that would map about a tenth of the sky and measure galaxy clusters as a probe of dark energy. It was clear that this should be paired with an optical survey of the same region.

We realized that such an optical survey could measure not just galaxy clusters, but also supernovae, growth of structure, galaxy clustering and gravitational lensing. The idea for the Dark Energy Survey grew out of that.

Our approach was to see what could be done relatively quickly and affordably by using an existing telescope at NSF Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile and building what would become, at the time, the world’s largest camera for a multi-year survey. We were able to bring together the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy to make this project happen.

How has SLAC has been involved in this process?

Risa: I first got involved in the Dark Energy Survey in 2003, when I was a postdoc at the University of Chicago and the project was just getting started. There were about 30 of us at the time. After we submitted the initial proposal, the collaboration began to grow slowly.

When I moved to SLAC in 2006, several people here with particle physics backgrounds were transitioning toward astrophysics projects like the Rubin Observatory and were eager to work on DES – it was clear that it would be beneficial to work on something with data sooner.

Over the years, DES became a real center of activity at SLAC, with multiple generations of students and postdocs contributing. Many early-career researchers now working on Rubin spent their student or postdoctoral years here working on DES and took everything they learned into this new survey.

Over the course of the survey, there have been many discoveries. What would you say were the highlights?

Josh: The first major discovery from DES was the detection of sixteen dwarf galaxies in our cosmic backyard. Even though Risa and her group had been thinking about dwarf galaxies, we didn’t design DES to find them; the survey was built to probe dark energy. It just happened that the survey we built to study dark energy was also very good at discovering nearby dwarf galaxies.

Risa: From my perspective as a scientist who does cosmological simulations, we expected lots of these little fuzzy systems around the Milky Way. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey had just started detecting the first of these objects before DES began. But as Josh said, DES wasn’t designed for this.

What we didn’t anticipate was how powerful these dwarfs would become as probes of dark matter. Over time, we learned how to use them to test aspects of dark matter physics that are otherwise very hard to access. At present, they’re the most sensitive probes of certain dark matter properties you can get from astronomical observations. It’s an exciting direction we’re pushing with next-generation surveys.

Josh: There are a number of other areas where DES has made important discoveries. One more recent thing I’d point to – I wouldn’t call it a discovery, but a hint. There are now signs that dark energy may not be the cosmological constant or this fixed vacuum energy. It may instead be something that changes over time.

If that’s the case, the first real hint that dark energy might not be constant came from the DES supernova results in early 2024. They were followed very rapidly by new measurements from the DESI survey of the galaxy distribution. And when you put those two things together, you start to get this indication that maybe dark energy is evolving.

We don’t know yet whether it’s a discovery. Rubin, among others, will nail that one way or the other. But to me, that was exciting because DES was planned to get the tightest constraints on the nature of dark energy that we could, and this brings us closer to that.

Risa: On the other hand, there’s a different story you could tell, which is that what we have learned so far is that we’re very, very close to this cosmological constant.

A Humanities and Sciences Professor and professor of physics in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University, professor of particle physics and astrophysics at SLAC, and director of the Kavli Institute for Particle AstrophysicWe’ve tested this model really well, and we’re just at the edge of seeing whether it breaks.

We’ve tested this model really well, and we’re just at the edge of seeing whether it breaks. We’re not sure yet. We’ll see more when we have more data. But it’s very close to this model we’ve had for almost 27 years now, the one we’ve been trying to break.

So far, I would say it’s not yet broken. We continue to make much more precise measurements, and we’re always trying to break things. I think all of us would be thrilled if these hints become a break, but we don’t know yet.

How will upcoming surveys like Rubin’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) build on DES’s discoveries, and what are you most excited about when it comes to the future of dark energy?

Josh: I’ve always thought of Rubin as the Dark Energy Survey on steroids: It’s bigger in every dimension. It will cover more sky, go deeper and observe with a much faster cadence that will uncover all sorts of transients. And the data volume will be orders of magnitude larger, making all the analysis challenges Risa mentioned even harder.

One thing DES did well was developing new techniques needed to analyze its data. Those methods will serve Rubin extremely well. Much of the groundwork for analyzing large surveys was laid with DES, and many of the techniques used in Rubin’s early years will be battle-tested DES techniques.

DES co-founder and associate laboratory director for fundamental physics at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator LaboratoryBecause Rubin is wide, fast, and deep, it will probe things we’ve never been able to study before.

Because Rubin is wide, fast and deep, it will probe things we’ve never been able to study before. In the time domain, it will essentially make a movie of the southern sky. I expect we’ll see rare, time-evolving phenomena no one has ever observed. And because it surveys such a large volume, it will find things we’ve only seen once or twice, like gravitationally lensed supernovae. We’ve seen only a handful; Rubin may find tens to hundreds, opening new avenues for cosmology.

Risa: I agree, DES helped us develop the tools we need for modern cosmology and for combining different kinds of measurements. Some of the analyses in the final DES results weren’t imagined when we started; they developed over time. Those techniques are exactly what we’ll bring to the early Rubin analyses.

For the “static” map of the sky, Rubin is similar in spirit to DES, just vastly bigger and deeper, with roughly an order of magnitude more galaxies. But the time-domain part – the movie of the sky – is completely new. DES had a very small version of this, but nothing close to Rubin’s scale or cadence. Rubin will open discovery space we’ve never explored. Some of that connects to dark energy, like finding many more supernovae, but much of it goes beyond that.

We expect to find many more tiny galaxies and the remnants of galaxies that fell into our own, and many new things that tell us about dark matter, galaxy formation, stars, black holes and even objects in our own solar system. What excites me most is the discovery space: the things we haven’t even thought of yet.

Support for DES includes funding from the DOE Office of Science and the National Science Foundation. More information on the DES collaboration and the funding for this project can be found here. DES used the NSF Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter telescope at NSF Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, a program of NSF NOIRLab, in the Chilean Andes. NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory, funded by the NSF and the DOE's Office of Science, is jointly operated by NSF’s NOIRLab and DOE’s SLAC.

For media inquiries, please contact media@slac.stanford.edu. For other questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.